Books for Kenya

While we were still on Loma Avenue we developed a friendship with Dick and Verah Johnson. I had a desk near Dick’s on the Collendale campus of Syracuse University and he was sort of a mentor to me. Sally and I got to know Verah and we would get together from time to time. Verah often had visitors in for a meal and one time she invited Sally and me for dinner when Steven Kioni was there. He was the Commissioner of Education in Kenya and was in Syracuse for a short time. In the course of the evening we found out that a serious shortage of books existed in Kenya, and we were very aware of the vast number of books sitting on bookshelves here in Syracuse. After Mr. Kioni left the Brulé’s and Johnson’s decided to try to gather books that were in decent condition and somehow get them shipped to Kenya and Steven Kioni.

The gathering of books proved to be very easy and soon Verah’s garage was overflowing with thousands of new and used books. We decided to paste into each book a little statement about books from Syracuse to Kenya. This statement said:

To The People of Kenya

This book has been enjoyed by some people in Syracuse, New York, USA

We hope it may be of some value to you as well

We looked over each book to make sure it was in good condition and we also discarded books which were purely religious in content. We called these “Blue Flame” books. All of this was going on over the winter of 1959-60 and much of it in February in the cold garage of the Johnsons. We would wrap up each evenings work with a couple of manhattans in the warmth of the Johnson living room. Mark was born nine months later.

The work of sorting and pasting went along quite well and we started to examine ways to get the books to Kenya. We looked for donations and Verah made contact with Bristol Myers and they volunteered to box them and ship them to a point in Baltimore associated with the Peace Corps since they volunteered to ship them to Mombasa, a major port in Kenya. It was then necessary to raise the money to get them offloaded and sent to Ruiru, the city in Kenya where Steven Kioni could pick them up. This cost about $400 which we were able to pay from local donations. This project was thus completed and it was so successful that once when the Vice President of Kenya was in Syracuse, and of course having dinner with the Johnsons, he told Verah he would appreciate it if we sent more books. We were out of the book business by then and Verah respectfully declined the suggestion.

Conversion and Life End

Those were busy times while we were in the Loma Ave. home. Sally had been struggling for some time with our religion differences and decided to talk with Father Culkin at St. John the Baptist church. She was willing to become a Roman Catholic but wanted to get matters straight before committing to the switch. Fr. Culkin almost blew it when he indicated the she would have to be conditionally baptized in order to complete the switch. Sally was always very proud of her membership in the Episcopalian communion – she considered herself to be an Anglo-Catholic. To go through another Baptism was a slap in the face to her feelings. But, she bit the bullet and decided to go ahead – I think primarily because of her agreement to raise the children as Roman Catholics. She talked this over with her good friend Marian Stanislaw who was a communicant at Calvary Episcopal Church, and also Father Konrad the pastor there. So the decision was finalized.

The next step then was to take the plunge to be re-baptized and we set up a date at St. John the Baptist for this to occur on March 12, 1960. On the day we got all ready to go and went outside to get in the car. As I was leaving the house I heard the phone ring and went back inside to answer it. It was a call from Sally’s mother from her home in Throop, NY. Sally’s father had just died. He was in his late 70’s, had earlier had a stroke, and had been in poor condition both mentally and physically since the stroke. After some discussion and consideration Sally decided to finish off the Baptism and then go to Throop to be with her mother. This she did and consoled with her mother for the rest of the day and the ensuing weeks.

The Syracuse Professional Sodality and the CIC

Later on we heard about a group called the Syracuse Professional Sodality and true to being a good convert both Sally and I decided to join it. This was a group that tried to strengthen the religious fervor of its members by meeting regularly, having religious services together and also attending an annual retreat. Mark Fitzgibbons was the (in)formal leader of the group which had been started by Fr. Dan Berrigan while he was at Lemoyne College. Fr. Dan had since moved on by the time we joined but there were several Jesuits we met including Fr. Dan Mulhauser and Fr. Bill Scott. Plus there were some really nice people we met who were members and they are still around.

When we went on a retreat we went to Mount Savior Monastery near Elmira, New York. This was operated by Benedictine monks and was a singing group. This is a picture of that place as it now appears. The Sodality would go there for a long weekend and it was an unforgettable experience. Silence was the order of the day. The men and women of the Sodality slept in separate sections of the monastery, but married couples could share a room. The days were filled with some lecture, study, and enjoying the beauty of the hills. The men and women took their meals separately, but the men had their meals with the monks. To me the highlight of each day was the evening service called Compline. This is a contemplative service that ended with the monks walking slowly into a basement grotto while singing a closing song. I found it to be very moving and look forward to going back there to attend that service. Our association with the group continued for several years but our interest waned. Especially around the time that Mark F. decided to give a lecture on angels and indicated how important it was to believe in them.

When we went on a retreat we went to Mount Savior Monastery near Elmira, New York. This was operated by Benedictine monks and was a singing group. This is a picture of that place as it now appears. The Sodality would go there for a long weekend and it was an unforgettable experience. Silence was the order of the day. The men and women of the Sodality slept in separate sections of the monastery, but married couples could share a room. The days were filled with some lecture, study, and enjoying the beauty of the hills. The men and women took their meals separately, but the men had their meals with the monks. To me the highlight of each day was the evening service called Compline. This is a contemplative service that ended with the monks walking slowly into a basement grotto while singing a closing song. I found it to be very moving and look forward to going back there to attend that service. Our association with the group continued for several years but our interest waned. Especially around the time that Mark F. decided to give a lecture on angels and indicated how important it was to believe in them.

Sally’s parents were very interesting and a study of contrasts. Alfa Corp, nee Alfa Monteith, was a large woman – not fat but sturdy. She smoked Regent cigarettes with a passion, drank heartily, and ran the show. She was born in the South – in Low Moor, Virginia. She was raised in the southern tradition and attended finishing school. As far as I could tell she was not a prejudiced person – she introduced us to the book “The Well of Loneliness”, the life of a lesbian. Also a gay couple, Art and Lennie, were within her group of good friends. Clarence Corp was born in Corfu, New York and received his Pharmacy Degree from the University of Pennsylvania. He was short and small man and a really hard worker. He operated his Pharmacy, the Corp Pharmacy, which was on the corner of State and Wall Street and thus next door to the Auburn State Prison. As with any small business person this meant that the children had to help with the operation of the store. The law required that a pharmacist had to be on duty whenever the store was open. This meant that during the depression where money was scarce the pharmacy was open long hours and Clarence would sleep in the back room and Sally would watch the store. She could not handle a sale, being quite young, so if a customer showed up she had to wake her dad. Her brother, Bob, had no desire to be a pharmacist and no desire to work in the store

At one time Sally and I drove to Low Moor to relive some experiences when she visited there as a child. One was the event which nearly ended her life. She was walking along a dirt road at her grandparent’s home and was bitten by a copperhead snake. Fortunately they immediately took her to a hospital and they were able to prevent any serious effects of the poison. She came that close to completely changing many lives.

The Corps would rent a cottage on Farley’s Point on Cayuga Lake, just outside of Union Springs, New York, and spend a couple of weeks there each summer. I was part of that all the time that I was around and it was great to visit there during the summer. A next door neighbor was John and Maud Hewitt, and John was an MD in Syracuse, New York. He was our family doctor while we lived on Loma Avenue. He was a very tall man – well over six feet, and they lived in a specially built house with extra high doorways.

Corp Pharmacy

As you can imagine the Pharmacy played an important role in the Corp family. Bob was sort of expected to take it over from his dad, but he had no interest in the place. Sally helped out in the store as a child. During the depression Clarence would spend hours there with little time at home. He would try to get some sleep and he would go into the back of the pharmacy to lie down. Sally would watch the store and wake up her dad if a customer showed up. This is a picture of the sign for the pharmacy that was over the front door. When Clarence retired and the building was sold to a new vendor this sign was sold to someone in Weedsport, NY. I tracked it down and finally was able to buy it for $75 from the person who acquired it. I hung it in our breakfast room at 212 Standish drive until I sold the house. I then gave ot to Bobby and Billy Corp – two of Bob and Rita Corps sons and they put it in their bar near Buffalo, NY.

As you can imagine the Pharmacy played an important role in the Corp family. Bob was sort of expected to take it over from his dad, but he had no interest in the place. Sally helped out in the store as a child. During the depression Clarence would spend hours there with little time at home. He would try to get some sleep and he would go into the back of the pharmacy to lie down. Sally would watch the store and wake up her dad if a customer showed up. This is a picture of the sign for the pharmacy that was over the front door. When Clarence retired and the building was sold to a new vendor this sign was sold to someone in Weedsport, NY. I tracked it down and finally was able to buy it for $75 from the person who acquired it. I hung it in our breakfast room at 212 Standish drive until I sold the house. I then gave ot to Bobby and Billy Corp – two of Bob and Rita Corps sons and they put it in their bar near Buffalo, NY.

When Clarence could no longer run his store they sold it and bought a small farm in Throopsville, NY in a valley they called Goose Hollow. Not too long after they moved out there Clarence suffered a stroke and never fully recovered. Alfa took lessons and learned how to drive a car so she was able to take care of their needs. Sally would drive out to visit them at least once a week, and she always was happy she had that opportunity. As I noted above Clarence died in March, 1960 and Alfa followed him about nine months later. She was living alone in Goose Hollow at the time and she died in early December as she was at her kitchen table addressing Christmas cards. The remains of Clarence and Alfa are buried in the Throopsville cemetery. Bob is buried in the same plot, and his wife Rita is in a plot next to Bob and his parents. Also, very dear friends of Clarence and Alfa, Joyce and ‘Nelkie’ Nelson, are buried in a plot just next to the Corp’s. Sally and I purchased two plots right next to her parents, and that is where Sally’s ashes are. Dolores and I have talked this over and when I am buried I will be cremated and at least some of my ashes will be buried next to Sally’s. Dolores can do anything she wishes with the rest of them. Dolores indicates that I can do what I wish with her ashes, should I be in a position to decide.

At the University I was able to finish my dissertation on time and had my oral examination late in May, 1958. It went very well but Sundarim Seshu asked a very embarrassing question. I had two distinct topics in my work and he simply asked why didn’t I just do more work in one of them and not spend any time on the other? As I remember I answered him truthfully – I was tired of the first one and so did the second one. After the exam was over he came up to me and said: “Congratulations DOCTOR Brulé!” I will never forget that. I finished the corrections in good order and graduated in June, 1958, and received a promotion from Instructor to Assistant Professor.

The following summer I finished off the research problem I had been working on that was sponsored by Bell Aircraft, so that phase of my life came to an end. I then started to get more involved with the University life and politics. I joined the faculty club, the ACLU and the AAUP-these at the behest of Norman Balabanian who was a founding father of the ACLU chapter in Syracuse. I took up golf and would play weekly with Don Kibbee, Chair of the Math Department and Phylis Kent, the wife of Gordon Kent in the EE Department. I scurried for financial support to pay for the research I was doing in the summer. Mostly this came from various military research organizations.

Around this time a research organization at the University of Illinois decided to move to Syracuse and set up their offices in the Skytop region of the University Campus. They assumed the name of the Syracuse University Research Corporation, SURC. They were completely funded by the military of course. It turned out that one of the chief researchers at SURC was Jim Rodems, a man I had met at Bell Aircraft. He worked on a different project at Bell than I did – the work was associated with designing an autopilot for helicopters. The war in Vietnam was underway and I found that they had money for control system work and since this was my field I worked with them in the summer also. I remember that I had two graduate students – one was Allen Durling. I was working full time in the summer and keeping my nose to the grindstone. One day I noticed that Allen had a tell-tale bit of sun tan on his hands. When one plays golf you wear a special small glove and the sun tan on his hands indicated that he had been playing a lot of golf. I thought to myself – what am I doing anyway?

Move to 212 Standish Drive

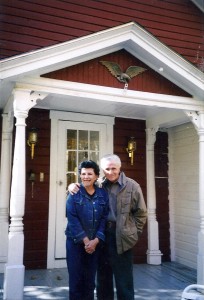

The move to 212 Standish Drive from Loma went very smoothly in spite of it being in the winter. Here is a picture of our house.

The move to 212 Standish Drive from Loma went very smoothly in spite of it being in the winter. Here is a picture of our house.

We seemed to have just about everything we wanted in the new house – room for our three children, a beautiful yard, a full basement and room for me to have an office. However the kitchen was quite old – it probably was the original and the house was about 30 years old. So we had that completely redone removing a wall and adding a counter. I then decided, with Sally’s help, that most of the walls in the house needed either paint or new wallpaper. So I became an interior decorator and attacked the walls with a vengeance. It all looked pretty good when we were through with this initial upgrading. The basement was empty of any junk and we decided we would try to keep it that way. So I took it upon myself to line one wall with shelving by building a framework along one wall and then attaching shelves. I figured that was enough shelf space to last a lifetime. Well, as a sign Sally had set up in the house said – “for every flat surface there is a pile of crud.” That was truer that we originally thought.

Our neighbors to one side were Joyce and Sid Goldstein. Below is a picture of them taken recently. They were a dynamic young couple – Sid was a business man and Joyce was a budding artist. Her medium was pottery and she was busy making all sorts of pots and other designs. She often had to go back to SU to fire her pots and so and one point she decided she wanted her own kiln. I was thrilled with this and it gave me an opportunity to try designing it. So I got a long length of light rope and hung it from the two ends thus forming a catenary. We adjusted it until it was the right height and width and then I traced the catenary onto a piece of plywood and then cut the plywood around the edge of the catenary. This served as a template for Joyce to build the kiln to the right shape. She succeeded in doing so and had a very good kiln.

Our neighbors to one side were Joyce and Sid Goldstein. Below is a picture of them taken recently. They were a dynamic young couple – Sid was a business man and Joyce was a budding artist. Her medium was pottery and she was busy making all sorts of pots and other designs. She often had to go back to SU to fire her pots and so and one point she decided she wanted her own kiln. I was thrilled with this and it gave me an opportunity to try designing it. So I got a long length of light rope and hung it from the two ends thus forming a catenary. We adjusted it until it was the right height and width and then I traced the catenary onto a piece of plywood and then cut the plywood around the edge of the catenary. This served as a template for Joyce to build the kiln to the right shape. She succeeded in doing so and had a very good kiln.

Here is a picture of a plaque that Joyce made for us in her new kiln.

Here is a picture of a plaque that Joyce made for us in her new kiln.

Some time after we moved in to 212 Standish Drive there was a lot of activity in the city around a program called “Urban Renewal.” The city fathers decided that the housing in the 15th ward, where most of the African American people –then called Negroes – lived should be removed. The program was called the “Negro Removal” program by many people. I listened to some of the news reports on this and wondered what all was going on.

We discussed this in meetings of the Syracuse Professional Sodality and tried to come to grips with the meaning of what going on. At this time there were no people of color in the group although it was mentioned that previously there was an African American woman, Dolores Morgan, that had been a member. We had heard that a march on Washington was being planned for late August, 1963 and part of the discussion was to determine what we, as caring Roman Catholics, should do. Mark felt that the march was not the place for us and I went along with that sentiment, so it was clear that Sally and I would not travel to Washington to participate in the movement.

When the march was over the newspapers were filled with pictures of the event and the outstanding speech by Martin Luther King, Jr. The emphasis in the Sodality on prayer, meditation and concern about whether angels existed seemed to be a rather strange way of life for me.

At the University our department had moved to Hinds Hall, and rather than being “squeezed” I had a nice office all to myself. I had been impressed with the inauguration speech of John Kennedy and I wrote across the top of my blackboard a quote from that speech – “Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country.” I sat at my desk and wondered what I would do in the spirit of JFK? This was in September, 1963 and there was picketing going on downtown against the Urban Renewal program around Pioneer homes, on Jackson street, so I left my office, got in my car and drove downtown. After I parked my car I joined the picket line. Thus began a new and worthwhile phase of my life which continues to the present time.

In early September, 1963, I had a private office in Hinds Hall. It was a corner room on the second floor and faced the main quadrangle. However, there was no window on that side, just a large blackboard. The other outer wall faced Machinery Hall where the University’s computers were housed.

I had just come through a rather rough summer for me. I was supposed to be doing research on something, and I’m still not sure what it was. My two PhD students had a good summer. One of them, Alan Durling, had a nice sun tan on his right hand – especially on that part of his hand where the opening on the standard golf glove is.

This was a summer of turmoil in the city. Mayor William Walsh had obtained Urban Renewal Funds and the inner city was being gutted. At least that part of it that housed most of the African-Americans of the city was being torn down. So people referred to it as “negro removal.” No funds were available to assist the displaced people in finding adequate housing. This was at least due in part to the fact that housing discrimination was rampant.

Such a problem was faced nation wide, and in his inaugural speech in 1961 President Kennedy had made the statement: “…ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” I had written this across the top of my blackboard, and on this day in early September I was leaning back in my chair meditating on the words. Gordon Kent dropped into my office and we discussed the meaning of the challenge. Some civil rights groups were picketing the area where the bulldozers were functioning, and I decided it was time I went down to Jackson Street and joined the forces. My first attempt to live the axiom: “Think globally, act locally.”

Joining the Picket Line

I drove down there and just joined the line, walking around the area. Lo and behold, soon after I saw Bob Belge arrived, and so I no longer felt entirely alone. There were about 20 people walking around and carrying signs – most of them were from CORE, but I also noticed one sign from CIC, the Catholic Interracial Council. After an hour or so of this I went back to my office in Hinds Hall, to sit and wonder- where is this going to lead me? What new paths will I now be following, or in my case, blazing?

Sally and I were still involved with the Syracuse Professional Sodality, (SPS), and when I mentioned at the next meeting that I had done some picketing I got little or no response. That group wanted to concentrate on developing spirituality, as was evidenced by their decision in August to not participate in Martin Luther King’s March on Washington. I asked around what the CIC was about and found out that they met regularly at the Bishop Foery Foundation, housed in a building on Forman Avenue. So, I went to the next meeting of the CIC. My life changed.

The CIC was made up of a small group of very active men and women; also several priests and nuns participated in different ways. The spiritual and emotional leader was Father Charles Brady. He had been appointed as City Missionary in 1946 by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Syracuse. In that capacity he become totally involved with the plight of the inner city residents, in particular the African Americans.

In the years before I joined, the CIC had done a number of things, including a survey of housing patterns and patterns of discrimination. John Murray was a driving force in this activity. I received an education about the problems in race relations in Syracuse and the situation involving schools and employment. My teachers were Rita Pomeroy, Rose Mannara, Dolores Morgan, the Lanigan sisters, Father Don Bauer, and many others, including Bill Chiles.

At this first meeting of mine I sat in the back and tried to blend in with the furniture. They were talking about a lot of things I knew nothing about – relations with CORE, the Niagara Mohawk Power Corporation, housing, schooling and the problems with the Board of Education, etc. Part way through this first meeting some woman suddenly walked in and created a bit of a stir. She lived across the street on Cedar Street and had come over to help with the meeting and the refreshments. I found out later that this was the famous Dolores Morgan.

This meeting served as an introduction to me of how to talk about things related to race and discrimination. Of course I had read about these matters, and in the Syracuse Professional Sodality even discussed them from an intellectual point of view. But now I was with people who lived it – either as victims of the discrimination or white people who were in tune with what was going on. So, I joined the CIC and went to their meetings and kept up my picketing. Sally and I were still members of the SPS so our plate was full with various meetings and gatherings.

Another person I met during this time was John Timothy Smith. He was a lawyer and had been overseas with the Peace Corps. At one point a City Court judge resigned, and John was appointed to fill the position. I guess he was a pretty good judge, so he decided that he would run for re-election. I remember we had several sessions around the breakfast table where we were addressing post cards and writing messages in support of his candidacy. He didn’t make it. However, our paths crossed many years later. I had heart by-pass surgery in August, 1991, and attended a cardiac rehab center during my recovery period. Coincidentally John was also there recovering from heart valve replacement surgery. So, we often had lunch together and struck up a friendship. I found out that John had a really strong temper – one time a car turned in front of him and a string of invectives just poured out. John died in June, 1998, and Dolores Morgan and I went to his funeral mass and interment. He was a fine man, and I got to know his sister Joan and brother Bob.

I continued to attend meetings of the CIC, and over the next few months I learned more about what was going on in the Civil Rights movement in Syracuse, and started to become more involved. I went to the meetings of the CIC regularly and came under the wing of Maryann Gibson and Rita Pomeroy. Rita was employed by the Bishop Foery Foundation as a social worker and had a great grasp of the situation. As we would discuss various problems and potential solutions Rita kept track of the bigger picture, and she would often warn – “Don’t throw out the baby with the bath water!” She was very concerned that the CIC would do something that would upset the hierarchy and tried to keep some sort of lid on things.

In early 1964, while Mary Anne Gibson was president of the CIC, an issue arose over the relocation of the Greyhound Bus station. The old one had to close – too small, and at first it seemed that the station would be relocated in the midst of the housing area where most of the population was black. The CIC took action on this, and much of the work was done by people like my friend, Bob Belge. In July he and several other people went to Cleveland to meet with officials of the Greyhound Bus lines. Greyhound didn’t want to admit bowing to pressure, but they became involved with looking at alternative sites after the appointment was made to see them. As an aside, another colleague and friend of mine, Ted Bickart, was involved through the Episcopal church and the organization ESCRU.

But the grandfather of it all was Bill Chiles. Actually, just about everyone addressed him as Mr. Chiles. He was a softspoken man who knew the problems of segregation and was a gentle, powerful, leader.

He knew well the separation of the races in Syracuse in all manners of employment, housing, and education. He was always with us to give support and guidance in our deliberations. He believed that one major problem was the lack of avenues of communication and he viewed the CIC as being one of those small voices trying to build the needed bridges.

I wondered how I would ever be able to come to grips with all the problems being considered by the CIC. Housing, integrated education, and employment were the keystones, and all interlocked. The Diocese of Syracuse decided to establish a Catholic Neighbor Training Program. (CNTP) This was an eight week program addressing all these issues, starting on April 6, 1964 with the Moral issue and finally ending on May 25 with an analysis of parish responsibility. The program was such that discussion sessions were integrated into each weeks meeting so there was some opportunity for things to sink in. I attended these meetings faithfully and became a brand new ‘expert’.

One of the main purposes of the CNTP was to get the parishes around the diocese involved with the civil rights movement. One thing many parishes did was to get speakers to come in and talk with them about the situation. Of course this had been going on before the CNTP, but I gather it picked up at the conclusion of the CNTP. I too got involved with this, first accompanying a more experienced person, like Dolores Morgan, and later I on I went out on my own.

This was quite a learning experience for me, as I had to come to grips with not only how I felt about this situation but also about what makes me tick. At the time I got involved with the Civil Rights movement I was a practicing Roman Catholic – mass often during the week, a retreat with the Sodality, and much thinking about religion and God. However, the glow around the Sodality was fading – certainly dimmed by their decision to not to participate in the march on Washington. My life was changing in other respects also – especially at the University. I had now been there long enough to get to know my colleagues as peers, and I had moved my contacts out into the University as a whole – I was President of the Faculty Club and active in Departmental and University politics. My home life was good and solid – the kids all adjusted to our new home on Standish Drive with Jim and Nannette in school and Mark an easy baby to take care of. Sally loved our house and the neighbors on the street seemed friendly and open.

As I mentioned, the CNTP was formed by command from Bishop Foery, and all the churches and pastors fell into line. I went around and gave many talks, and they were heavily interlaced with biblical references and based upon Christian morality. For example, in July, 1964 when speaking about the parable of the good Samaritan, I said: “When we realize that the only road to salvation lies along the path of the good Samaritan, then the full meaning of the parable will unfold before us. For it was not that the good Samaritan gave the most—not at all. The beauty of this parable is that it was the good Samaritan who received the most. … What he received was the greatest of all gifts—God himself. … So it is with us. It is not that the Negros need us—we need to give of ourselves.” So this went on for the time I was involved with the CIC.

Shortly after the end of the formal part of the CNTP I began a long period of answering invitations from various groups to talk about the program. So, here I was, an expert already. I went out to the suburbs, went to some social groups, and at one point participated in a similar program at the Cathedral in Syracuse. My involvement grew!

In the Fall of 1964 I was elected President of the CIC and my involvement increased. There was a myriad of issues to be addressed by the CIC, and I became involved with many of them. One interesting issue grew out of the picketing and pursuit of the Niagara Mohawk Power Corporation. CORE had originally started this, and it spread throughout the Civil Rights groups in the area. Basically the push was to get the NMPC to hire more blacks, even at entry level jobs. The main demand was to get black meter readers hired and NMPC used the crutch of demanding a high school diploma to keep from hiring blacks. Nepotism was strong there-you could get a job if someone you were connected with was already there. At one point several demonstrators were arrested for trying to climb a fence. Their case appeared in City Court, and the prosecution delayed the trial by various procedural motions. Finally the case came before John Timothy Smith. John had gotten the appointment to Judge partially because his father, also John Timothy Smith, was a power in the Republican party. Well, John took the bull by the horns and dismissed all charges against them. John never made it in the next election to keep the seat, but he made it into the hearts and minds of the local activists.

Another fascinating individual I met during this period was Fr. Donald Bauer. He indeed was quite a character. At various times he was pastor of several different churches in the diocese, but while I knew him he was at the church in South Onondaga. He was a busy activist, always on top of things and wanting to do more. He would picket and be supportive of such actions but he wanted any priest that participated to be sure to wear a hat. The Bishop wanted this and Don Bauer tried to walk a careful line on how far out he would go. He was very pro-union, pro civil rights, absolutely anti-abortion, and prepared to go public on issues that were important to him. We would have a meeting at the Bishop Foery Foundation laying out our plans and Don would stop by my home to put the finishing touches on a press announcement, or some other public document. He and I would work on my computer into the wee hours of the morning getting every statement into perfect order.

Many things were happening at this time, one being the opening of a Community Action Program at Syracuse University. This brought many more people into the area, including the powerful Saul Alinsky. Others rose up too, such as Chris Powell. He was concerned about what to do about the construction of route 81 in the city. He thought perhaps that the space underneath it next to Pioneer Homes could be used for educational purposes. I was busy going around giving speeches, writing letters to activists around the country, and in general poking my nose into many unfamiliar places.

One other visitor to Syracuse was John Howard Griffin. He is the author of the remarkable book, Black Like Me. He took medicines that would change the appearance of his skin so that he took on more of an African-American hue. He stayed at our house the night of his lecture and he was indeed a remarkable man.

While all this was going on Sally was busy with the children and maintaining the household. I would come in from a meeting or a talk and be all fired up. To relieve my stress I started painting, by the numbers, a lemon tree on an entrance wall of our house. A little bit every few days, and it soon started to take shape. Sally did not participate with the same intensity as I did in all these activities, so this was stressful for her. This stress mounted as we went into 1965, especially with regard to what happened in and around Selma, Alabama. My involvement in this matter was very intense, and look to the section of this document labeled “Selma, Alabama” to see what happened there.

One other event that occurred in my neighborhood involved a neighbor across the street. This was the psychiatrist Larry C. At one point the CIC encouraged people to take actions that would increase the possibility that a black family could move into a currently all-white neighborhood. One way to do this is to let our neighbors know that we want to have a welcoming neighborhood. So, the CIC printed up some post cards that we would mail to our neighbors when a house came on the market. The C’s house went up for sale and so I filled out the card which said that Sally and I “welcome all good neighbors regardless of color.” I mailed such a card to all the homes in my block.

A short time later, like a week or so, I received a letter from a lawyer, Edward B. Alderman, directing me to “Cease and desist in interfering with the efforts of the real estate salesmen to sell the C’s residence.” (dated March 25, 1965) Wow! Somebody is paying attention. This was such a delightful letter that I took it to my lawyer friend Vince O’Neil who is also a member of the CIC. He hooted when he read it and said something to the effect: “Let me handle this. I know the lawyer who wrote it and he is a hack. The Bill of Rights still is alive and well and he needs some education.” That was the last I heard of that particular issue.

The number of issues faced by the local community seemed endless. Employment, as exemplified by the situation with Niagara Mohawk Corporation, needed much improvement. Housing, as exemplified by my neighborhood situation, was in bad shape. Education was in about the same sad situation. The public schools were highly segregated, as people of color attended one set of schools and the rest of the population another set. Busing was proposed as a means of eliminating segregation, but was viewed as anathema. Also the parochial schools of the Roman Catholic diocese were segregated in that the student body included very few black people. So, what could the CIC do? I believed the Catholic schools were part of the problem. So, on my own I wrote a letter to the Editor of the Newsletter of the CIC proposing an action for the parochial schools.

The public schools were proposing a so-called Campus Plan to improve education an eliminate segregation. I proposed that parochial schools could pair off with public schools that are predominately black, such as Sumner, Danforth and others. As a second step, encourage cooperation with the Campus Plan by closing the parochial schools and sending the children to the Campuses. This created a bit of a stir. My letter was published in the Newsletter, and I guess Father Brady had to explain to the Bishop what person wrote this. I remember at one point in the spring of 1966 I offered to resign as President of the CIC, but this wasn’t accepted.

Around this time my attempts to get support to go overseas with my family and to teach in a developing country proved to be successful, and that led to the next phase of my life. Marshall Nelson was elected President of the CIC following my leaving Syracuse.

Selma

March, 1965

I am 38 years old, and tomorrow, Saturday, is my birthday. Just last Sunday, the 7th, hundreds of people in Selma, Alabama, had assembled to seek the right to vote. On that date the marchers in Selma began their walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge toward the state capital, Montgomery, which is 50 miles away. The people, most of whom were Negro, were attacked by state troopers and policemen who, “swinging clubs, whips and ropes chased screaming, bleeding marchers nearly a mile back into Selma and clubbed and charged them with horses as they ran.”

On Monday the Catholic Interracial Council (CIC) met with other groups and endorsed ..”any appropriate peaceful action by any group who has the courage to march against this vicious action.. “. Then on Tuesday Reverend James Reeb and 2 other Unitarian Ministers were assaulted in Selma, and on the11th Reverend Reeb dies.

As I sit at my kitchen table with my dearest friends from the CIC, including Sally, Fr. Brady and Dolores Morgan, I wonder What can I do? I feel I must go to Selma and be a part of the moment of history. The people at the table support my decision. So, early today, the 13th and my birthday, I fly out of Syracuse. I must change planes in Washington for a flight to Montgomery, Alabama. In the terminal I see George Wiley, a long time activist who is a Chemistry professor at Syracuse University. We greet each other, and George asks, “Why are you here in DC? ‘Well, George”, I reply, “I am heading for Selma. The situation seems terrible there, and they are asking for people from around the country to join them.” George says: “John, that’s fantastic. “We’ve got to get more information about what is actually going on in Selma — will you call us? It seems like an act of God to find you!” Now I can feel the tension building up in me.

My plane is announced as “Richmond, Atlanta, Intermediate stops, Mobile.” Now I am an intermediate stop on my life’s journey. What will go on there? Why am I so emotional? I had better settle down soon. During this flight I feel a ball of fire form in my chest. We are high above the clouds, and I am aware that well below them is conflict and pain.

The plane arrives in Montgomery on schedule, and as I leave the terminal I see a van marked “Catholic Mission.” Three other people are gathered around and the driver says he will take all four of us into Selma. “The compound around Brown’s chapel is ringed with police, but I know where there are gaps and I’ll get you in safely,” he says. We are on Highway 80 to Selma, and a pickup truck with a GOLDWATER ’64 sign on it passes us. As it goes by the passengers in it give us vicious stares – we also notice that a shotgun is mounted in the rear window of the pickup. The ball of fire in my chest is gone. I am truly doing the right thing. We pass a sign for: “Torch Motel for Colored Guests.” We are now in Loundes County and 20 miles from Selma. A state police car passes us going in the opposite direction, and our driver slows perceptually. The driver of the van tells us – “just go to Brown’s chapel after you leave the van. People there will find a place for you to stay.”

Now into Selma – the driver skirts around some buildings and we are in the compound. Police all around us. Helmets. Taunting from the police and the crowd behind them. “Go back to where you came from.” “Outside agitators aren’t welcome. You have no business here.” Many people walking and talking. I head for the Chapel, and climb the steps into it. It isn’t very large, will hold maybe 500 people at most. All around there are groups of people talking, and I see a table marked “Housing.” The woman staffing the table greets me cordially and says: “Welcome to Selma. Can I help you with anything?” So, I let her know what I want, and she says “Mary Lamar has room for one more. Here is her daughter, Linda, and she’ll show you where her rooms are.” So I take her hand and off we go through the gathering dusk.

Mary’s quarters are just around the corner from the chapel. Linda leads me into the apartment, and I meet her mother. “Welcome to Selma,” Mary says. “We are so happy to see people come here from outside of Selma.” There are several people sitting and talking, and she introduces me around. Then she shows me where I can put my backpack on a bed in the corner of one bedroom. I join the group, and we engage in small talk, like saying where we are from. I am the only “outside agitator” in the room – all the other people are residents of the project in Selma.

Late in the afternoon there is a meeting in Brown’s Chapel. Leaders from SCLC and SNCC give information about what the plans are, and the problems they are working on. A little boy comes into the Chapel, bleeding from a head wound. This was caused by something that fell off the front of the Chapel.

I can hear the singing at the all-night vigil along the police lines. Only a token police force is left. The chanting grows louder. Oh, God. Stay on the line.

It is now Sunday. I slept well, and had good conversations with the people in Mary’s house. I also called George Wiley. I let him know that more people are needed – desperately. I go out to the line, and stand facing the police, with all the hatred they display. I met other residents of the compound, and had breakfast with them. The troopers have been reinforced, and now there are more troopers than demonstrators. The local paper indicates that starting tomorrow morning arrests will be made rather than a physical restraint by the police.

Back on the line there is quite a bustle. The police have a supply of saw-horses and planks, and are attempting to build a wall around the compound. We all start singing — “Love will tear it down”, and it actually does collapse. (Rotten timbers helped.) Back in Brown’s Chapel there is much discussion going on. Something is up for tomorrow. It turns out that there is concern that the police will arrest everyone on the line at that time. Back on the line, the demonstrators are taunting the police. But, Hosiah Williams steps in and gives a talk about the symbolism of the wall.

An announcement is made that tomorrow all the citizens of Selma will be permitted to go to the Courthouse. This is followed by15 minutes of singing AMEN, AMEN. A man I meet in Lamar’s house looks at me and says: “it’s worth a million dollars to me to see your face here.” Tonight they are looking for volunteers to stand at the barricades. I will take the 1:00 a.m. to 5:00 a.m. shift. It is cold and I have a heavy overcoat on. The police have bright lights on us, and they appear to be angry. I pull the collar of the coat up as high as I can. I can hear dogs barking in the distance.

It is Monday and things are quiet. The vigil is small, and the wall is gone. The clergy who are demonstrators are all lined up in front of the First Baptist, and will march as far as they can towards the Courthouse. All police are off the street now, and preparing to make arrests. There is much conferencing and discussions going on amongst the leaders. Sheriff Clark announces: “All Selma residents who have voter registration business at the Courthouse may proceed.” There is much confusion. Some shout: “We all have voter registration business at the Courthouse!” The police of the city replace the sheriff’s men and the Captain says: “No city in the nation would permit you to walk five abreast and disrupt.” There was then much talk and discussion and meetings.

It is now 10:45 a.m. There is much singing, but also a power struggle between SCLC representatives and SNCC. The problem is that both the Selma demonstrators and the “outside agitators” must be satisfied, and this is extremely touchy. At 12:30 there is a memorial service for Rev. Reeb. Martin Luther King, Jr. is here. During the benediction we can hear “We Shall Overcome” drifting in from the line.

The announcement then came that we can march to the Courthouse today. I march with Fr. Dan Berrigan, and the line stretches for miles – 3 abreast. A woman’s faces us from a store and she spits at me and Fr. Dan. There are catcalls along the march, but mostly it is deathly quiet. Along the way Negro teenagers approach me and bashfully ask: “Do you have someone to march with?” I see Fr. Konrad and Fr. Vermilyea – they ask, “Where are the Roman Catholics? The Anglicans came – where is the Roman Catholic leadership? Shame!”

That night we listen to President Johnson’s speech. “But about this there can and should be no argument. Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote. There is no reason which can excuse the denial of that right. Yet the harsh fact is that in many places in this country men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes.” What a gift of God to be sitting in Ms. Lamar’s living room in Selma, Alabama and to hear those words!” His speech had many of the same words as the speeches I had heard in Brown’s Chapel.

The next day I woke up happy, and saw parts of Johnson’s speech again. I chatted with friends I had made there, and said goodbye to them. Now I am on the bus to the airport in Montgomery, and I feel lonesome for the first time.

Aloft. Life has ended, and begun. Such people I have never met before. But just think what is happening to them. What now? Anger – lack of organizational commitment. Joy – sense of belonging. Work? People must know that in our hands lie the tools to shape the new society. We are not hurt enough nor angry enough. Who said: Sick with a disease only white men can catch? The colors are so warm.

Back to Syracuse

As I deplane in Syracuse I meet Frank Durgin as he is walking to catch a flight. It turns out that he too is headed for Selma, and I give him my best wishes. Then I meet Sally and now I am home for sure. We talk things over and it seems that while I was gone there was a lot of talk on the street about me being in Selma as an “outside agitator.” The general feeling seems to be that I am only making matters worse by my actions. I feel that I must face my neighbors and talk this over with them.

I first visit with Dean and Mrs. F. who live across the street. He is the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Syracuse University. I called them and said I would like to come over and talk with them, and they invited me to do so. They repeated the usual thing about being an outside agitator. I then went to our next door neighbor, the S’s and got the same scolding. But, I hold my temper and try to calmly explain to them why I feel it is so necessary to participate in this action. We have so far to go in this country to really believe in democracy.